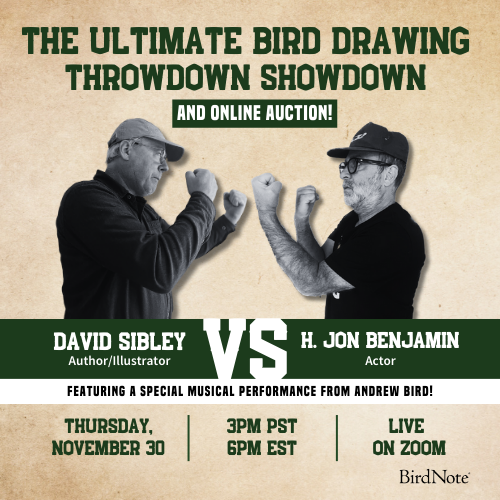

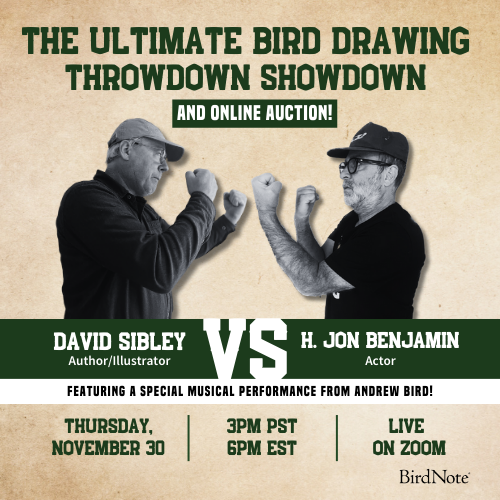

Join BirdNote tomorrow, November 30th!

Illustrator David Sibley and actor H. Jon Benjamin will face off in the bird illustration battle of the century during BirdNote's Year-end Celebration and Auction!

What is it about Black-backed Woodpeckers and fire?

Audubon's Alisa Opar wrote in an earlier blog: "Black-backed Woodpeckers are perhaps the most iconic of post-fire species, since they’re wholly reliant on burn zones."

Maya Khosla now shares with us her experience of surveying a post-fire area, in search of Black-backed Woodpecker nests:

If you have ever tried to find nesting Black-backed Woodpeckers (BBWO) in the Sierra Nevada-Cascades Region, you probably know two things – they are rare, and your chances of seeing one are highest in forests recently rejuvenated by fire.

Recovery © Maya Khosla

May of 2015, about 21 months after the "Rim Fire" roared through parts of Yosemite and Stanislaus National Forest, our quest began. Dr. Chad Hanson selected two post-fire areas within Stanislaus as research plots for his long-term woodpecker study. His team of seven biologists covered them edge to edge. I was among them.

The place and the process

Western Bluebird © Maya Khosla

One of our plots was greener than the others. Most of the fire-brushed trees were alive, and few had turned into snags – standing dead trees packed with insect larvae that serve well as woodpecker food. We detected no BBWO there.

The other plot was a forest full of snags and new plant growth. At dawn, it looked like an expanse of black ship masts. By the time the sun’s shafts had reached our knees and boots, the ship masts looked afloat in a bright sea of leaves: miner’s lettuce, dogwood, paintbrush, saplings of oak and conifer. Renewal was in full force, typical for post-fire forests of the American West when left to themselves. We had to focus through the puffs of detritus dust bursting up with every footstep, to avoid trampling on saplings.

We spent the morning hours between 6 a.m. and noon, the protocol survey period, generally walking alone in order to cover more ground. But by the sixth morning, we were spent. We had found a multitude of nests – of Western Bluebirds, White-breasted Nuthatches, Mountain Bluebirds, and Mountain Chickadees, all using woodpecker cavities. But not a single Black-backed Woodpecker nest.

“I’ve been birding for about 35 years,” mused Craig Swolgaard, a wildlife biologist retired from the California State Park system, “and Black-backeds aren’t birds you see every day. They’re not common like the White-headed Woodpecker or the Hairy.”

We know they're here...

© Maya Khosla

But signs of Black-backed Woodpeckers were everywhere. We had seen trees full of their deep drillings. We’d played songs according to search protocols and heard the soft “chup-chup” of their answers. We listened to their territorial rapping on hollowed wood for three-plus seconds at a time – resonant as the clatter of drums. Glimpsed flashes of gray and white under-wings catching the sun as they flew, and watched carefully as they alighted.

“Once it lands on a burned tree and turns its back to you – that full black back – it just disappears! You think ‘where’d that bird go?’ The camouflage is incredible,” Kevin Kilpatrick laughed his exasperation away. He was the first to find a Black-backed nest cavity during our 2014 surveys. Now it was May 25, 2015, a week into our second season, and no nests had been found.

Getting warmer...

© Rachel Fazio

The nesting survey protocol includes three separate searches in each study plot. I joined Craig for the third and last. We traversed a transect, and he played calls at regular, 200-meter intervals. A male Black-backed with bright gold feathers on his head responded by rapping. Then he took off.

The area looked special. The snags the bird had clung to were so rich with woodpecker holes that we doubled back after completing the following transect. Craig was in the middle of playing a call when a male BBWO – possibly the same one – came speeding in our direction. He landed on a charred tree trunk nearby and his head oscillated back and forth, investigating us. Apparently content, he embarked on an assiduous search of his own, whacking the trunk. Within a minute and a half, he had pulled out a noodle-like larva (a wood-boring beetle) and realigned its flailing body to fit tightly within his beak. Then he took off without eating.

That was a strong sign. We dashed after him, trying to contain ourselves, excited about the possibility that he was about to feed young woodpeckers.

And still warmer...

Running uphill through a reviving snag forest is tricky at best. In contrast, the male took an effortless zigzagging path, stopping at snags to look back. We had no chance of catching up with him. Far uphill, we saw him dive. He landed on a medium-sized snag, sidled horizontally around it, and disappeared. After a short interlude, we saw him rise into the air. He followed a similar zigzagging path with such efficiency, we couldn’t tell if the larva was still in his beak.

Now he was gone. Utterly deflated, we advanced toward the area where he had flown low. It seemed almost impossible to find the snag he had favored just moments before.

That’s when we heard them.

Success!

Black-backed Woodpecker male © Maya Khosla

One of the tree trunks was shrilling with cicada-like sounds. Cicadas or young Black-backeds?

We looked around the corner and found the answer. It was a round, perfectly beveled woodpecker cavity about eight feet off the ground, ringing with the cicada-like cries of newly hatched Black-backed Woodpeckers. They must have hatched just a day or two before.

We crouched behind a snag some seventy feet away and waited. Soon the male flew back. The shrilling grew in intensity. He cast cautious glances around and climbed in.

His young were still too small to poke their beaks out. About a minute later, the male emerged with a fecal sac in his beak.

The cavity was just a few feet into the plot’s southern boundary. The whole team celebrated that afternoon.

###

Alisa Opar wrote in the blog, Wildfire Benefits Many Species: "Black-backed Woodpeckers are perhaps the most iconic of post-fire species, since they’re wholly reliant on burn zones. They forage at smaller, charred trees, but when it comes to finding a home, they single out trees with previously decayed heartwood - nicknamed “spike tops” - where they excavate their nests the year after a fire. Just how they locate freshly charred forests is a bit of a mystery. Beetles are attracted to smoke and emit pheromones, and the woodpeckers might follow their chemical trail. Or perhaps they simply chase the flames, says Dick Hutto, a University of Montana professor who has studied the birds for nearly 20 years. 'It’s not that hard for us to pinpoint a fire,' he says, 'and they can fly.'”

Black-backed Woodpeckers move on after three or four years, tied to the boom-and-bust cycle of beetles.

Listen to BirdNote shows about Black-backed Woodpeckers:

Woodpeckers and Forest Fires

Woodpecker Wonderland in Washington State

Instrumental Bird Sounds