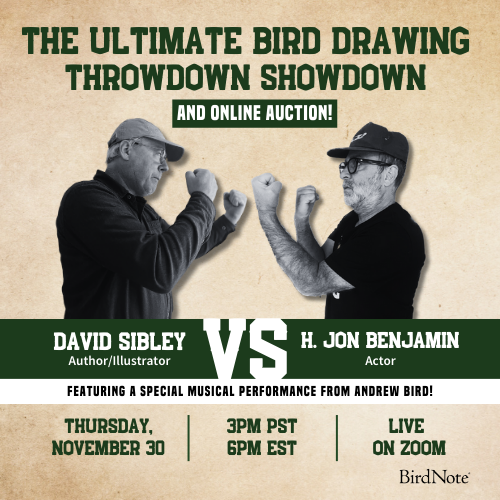

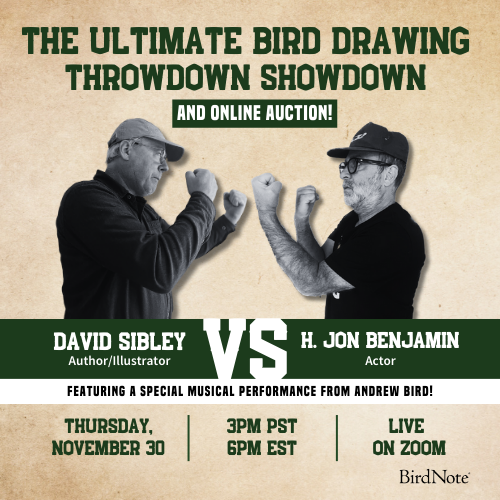

Join BirdNote tomorrow, November 30th!

Illustrator David Sibley and actor H. Jon Benjamin will face off in the bird illustration battle of the century during BirdNote's Year-end Celebration and Auction!

Suzanne Tomassi, vice president of the Puget Sound Bird Observatory, talks about the rhyme and reason to banding birds...

One of the benefits of banding, which is a mark-recapture technique, is that it gives us the opportunity to assess “vital rates,” measures such as survival rate, recapture probability, and recruitment. These data are useful in:

* Identifying species that might be facing environmental pressures

* Identifying “sources” and “sinks,” (respectively, high quality habitat that on average allows a population to increase, and low quality habitat that, on its own, is unable to support a population)

* Clarifying other population dynamics that are used to inform conservation decisions

The Identification Guide to North American Birds, or the “Pyle guide,” is the bander’s ultimate reference. It collates everything we know about a species’ characteristics, including age, sex, size of certain feathers and body parts, color variation, et cetera, in a way that helps us gather as much information as possible about the bird in our hand. Each bird presents a small puzzle, providing cues and clues that we use to determine whether the bird is male or female, how old it is, its health, and if it is in breeding condition. Of course, since banding is a mark-recapture technique, we already know something about our bird if it has a band from a previous capture on it.

Let’s start at the beginning - let's say we just caught an unbanded bird. Here’s an example of how we might work through the age puzzle, piecing together clues using our Pyle guide. Say Pyle tells us that a species we are examining normally molts (replaces) all or most median and greater coverts (these are feather tracts on the wings) and no tail feathers or primaries and secondaries (the long wing feathers) during its very first molt after hatching. Pyle might tell us that this first molt occurs on the bird’s wintering grounds. Then in spring, suppose we catch a bird that has pale, tattered tail and wing feathers, but contrasting fresh-looking coverts. We can guess that the fresh feathers were replaced, while the old feathers are worn from winter and migration. Pyle then tells us that, subsequent to that first molt, the species molts all its feathers every year. We can conclude that the bird we are holding is starting its second year, having hatched the year before.

It sounds straightforward enough on paper, but the subtleties quickly become apparent in the field. So we use as many clues as we can. We might be able to see “windows” in the skull (viewed through the skin) where it has not yet pneumatized, implying a “hatch year” bird. There might be other clues to age - How worn are the feathers? Does the bird have any characteristic juvenile traits that might tell us it just hatched? These might be a yellow edge to the bill (or “gape”), loosely textured feathers, an eye color different from that of an adult of the species. Does it have a “brood patch,” indicating that it might have young in a nest, or at least that it’s an adult making an attempt at breeding? We gather as many clues as we can and make an age determination. Most passerines can be reliably aged only as hatch year, second year, or after-second year.

All banders send their banding data to the Bird Banding Laboratory at the USGS, so any banded bird can be identified. Every band is accounted for, and every banded bird has added to our base of knowledge.

The brown feathers on the outer edge, retained from hatch year, indicate a second-year bird by the contrast with newer, replaced feathers. (There are actually three feather generations in the wing above – see labels below of a similar situation.)

Note the difference in feather structure between juvenile (brown, more loosely textured) and basic (darker, lighter) feathers.

Females (and sometimes males) form a vascularized “brood patch” to keep eggs and chicks warm. It is a key in both sexing and ageing.

The banding table, with Pyle guides open.

###

Listen to a BirdNote story about banding birds at the PSBO.

Puget Sound Bird Observatory studies birds and their habitats in the Pacific Northwest to better understand changes in bird populations, to inform decision makers, and to engage the public with birds and their needs. Learn more!

Here's a show about Banding Hummingbirds.

Report banded birds at ReportBand.gov. That's the Patuxent Wildlife Research Bird Banding Laboratory.

Seen an American Crow with legbands? Learn about what to report -- and how -- at UWCrows.